How do you read utility patent claims?

What exactly does a utility patent cover? It boils down to the claims. Yet, they are the least understood. Attempting to understand utility patent claims can feel like learning a foreign language. You’ll see a lot of funky claim language like “comprising,” “said” and “wherein,” not to mention the hierarchy of independent and dependent claims.

Want strong patent claims that will actually stop competitors from copying you? Contact US patent and trademark attorney Vic Lin at vlin@icaplaw.com or call (949) 223-9623 to see how we can help you file a flat fee patent with stronger claims.

This short guide will hopefully provide some clarity and a helpful framework for understanding utility patent claims.

Where are the patent claims located?

The patent claims are located at the end of the written specification. They begin right after the section entitled Detailed Description of Preferred Embodiments. Claims are numbered, so Claim 1 will always be independent.

What is an independent claim?

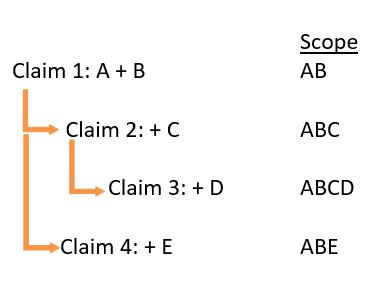

An independent claim contains a preamble that does not recite another claim number. Claim 1 in a utility patent will always be independent. The following is a diagram of a claim set where Claim 1 is independent and Claims 2 to 4 are dependent:

For example, suppose the claims after Claim 1 look like the following:

2. The device of claim 1, further comprising. . .

3. The device of claim 2, further comprising . . .

In the above example, claim 2 depends upon claim 1. Claim 2 is dependent. Claim 3 depends upon Claim 2 and adds further elements.

Notice how Claim 4 depends directly on Claim 1. That means whatever is recited in Claim 4 would be tacked onto the limitations of Claim 1. Claim 4 would not include any of the features recited in Claims 2 or 3.

If there were a new claim 5 that did not depend on any other claims, Claim 5 would be a second independent claim that would start a second claim set.

What does an independent claim cover?

To determine the scope of coverage of an independent claim, pay attention to each paragraph after the preamble that starts with “A” or “An” and ends with “comprising:” and a hard paragraph break. Everything after the colon matters.

In order to infringe a patent, a product must infringe at least one independent claim. To infringe an independent claim, the product must contain at least each and every element of the independent claim. Having more than what is claimed does not avoid infringement. Infringement is avoided if the product is missing a claim element. If the product omits at least one claim feature, there is no literal infringement. However, there still might be infringement under the doctrine of equivalents (DOE). So, it’s important to explore whether the product has the equivalent of a missing claim element.

Less is more?

Suppose a utility patent has two independent claims. The first independent claim recites a product having two features, AB. The second independent claim recites a product having three features, ABC. Question: Which independent claim is broader?

Answer: The first independent claim because it requires that a product have only two features, AB, to infringe. The second independent, which recites an additional third feature, is narrower in scope because an accused product must also include feature C in order to infringe. If a competitor were selling a product with only features AB, the product would infringe the first independent claim, but not the second.

It may seem counterintuitive, but having an independent claim that “covers” a whole bunch of features (e.g., let’s say 8) might actually be quite narrow in scope. A competitor could design a product that includes only 7 of the 8 claim elements and thereby avoid infringing that independent claim.

What is a dependent claim?

A dependent claim hangs from an independent claim and recites further features or limitations. In other words, a dependent claim gets more specific and, thus, narrower in scope. Secondary features are typically written into dependent claims, whereas the independent claim usually recites a combination of primary features.

A basic logic of patent infringement is that if a product does not infringe an independent claim, then the product automatically would not infringe any claims dependent upon that particular independent claim. So if it is determined that a product does not infringe an independent claim, then do not bother analyzing the dependent claims in that claim set.

Why bother having dependent claims?

An astute reader may ask, “What is the point of dependent claims if they cannot be infringed once you knock the independent claim?” It’s a good question. One important purpose of dependent claims is that they provide backup in case the validity of the independent claim is attacked.

In the above example, suppose the prior art already shows a product with features AB.

What is a claim set?

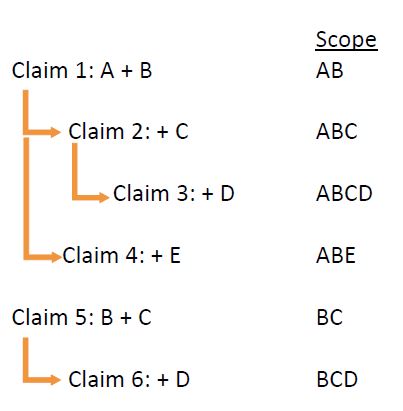

A claim set consists of a single independent claim and all the dependent claims that depend upon that particular independent claim. To illustrate, there are two claim sets in the following example:

- An apparatus, comprising …

- The apparatus of Claim 1, further comprising . . .

- The apparatus of Claim 2, wherein . . .

- An apparatus of Claim 1, comprising . . .

- An apparatus, comprising . . .

- The apparatus of Claim 5, wherein . . .

In the above example, Claims 1 and 5 are independent. Also, notice how dependent Claim 3 depends upon dependent Claim 2, which means that the scope of Claim 3 includes everything recited in Claims 3, 2 and 1.

In contrast, dependent Claim 4 depends directly upon independent Claim 1. So the scope of Claim 4 contains everything in Claims 4 and 1 (but not Claims 2 or 3).

Since Claim 5 is independent, Claim 5 is the beginning of a second claim set that includes dependent Claim 6.

Why have more than one claim set?

Let’s take another look at our claim tree where Claim 5 starts a second claim set:

Notice how independent Claim 5 has a different scope than that of independent Claim 1. Suppose a competitor made a product that contained only features B and C. Such a product would not infringe Claim 1 or any of its dependent claims. Therefore, the value of additional claim sets is that you get to start with an independent claim with a different combination of features.

Since the USPTO filing fee for a utility nonprovisional application lets you have up to 3 independent claims and 20 total claims, we typically try to draft utility applications with three claim sets. Since we’re paying the USPTO, we might as well get our money’s worth.

How do patent examiners review claims?

In each claim set, patent examiners start with the independent claim by looking for each claim element in the prior art. If the examiner can find all the elements in the independent claim, the examiner will reject the independent and move onto the dependent claims.

Need help with your patent claims?

Need to file a utility patent application or review a patent? Are you concerned about infringement or whether your idea is patentable? Email registered patent attorney Vic Lin anytime at vlin@icaplaw.com or call (949) 223-9623.

If you’ve found this post helpful, you might enjoy reading our list of best IP resources.

Want to learn more?

Sign up for a free email course on the patent process.