What is the design patent infringement test?

It’s simple to recite, but tricky to apply. The test for design patent infringement involves a visual comparison between the patented design and the accused product. Known as the ordinary observer test, the standard for determining design patent infringement basically asks whether the accused design would appear substantially similar to a patented design to the eye of an ordinary observer.

What can be so hard about looking at two designs and determining whether they appear substantially similar to an ordinary observer? Well, there are various defenses and exceptions to the rule that must be considered.

Need help enforcing design patents or avoiding infringement? Contact US patent attorney Vic Lin at vlin@icaplaw.com or call (949) 223-9623 to see how we can help.

Does the accused product have to include the point of novelty in order to infringe?

No, the accused product does not need to include the point of novelty of the patented design in order to infringe. Also, the prior art must be considered when determining infringement.

Who is the ordinary observer?

As defined by the Federal Circuit, the “ordinary observer” is someone who would be familiar with the prior art. Practically speaking, it means that the ordinary observer knows that what designs already existed before the filing of the patented design. Therefore, if an accused product seems very close to such prior art designs, there is a decent probability of no design patent infringement.

Design patent infringement: What does not look substantially similar?

How similar of an appearance is too close? The issue is whether the accused product would deceive an ordinary observer to suppose it to be the patented design. Those familiar with trademarks will notice a touch of resemblance with the likelihood of confusion standard.

Is that all there is to design patent infringement? Whether an observer would be deceived to think an accused design is the patented design? Actually, there’s more to determining design patent infringement. You have to take into consideration the prior art and any functional aspects of the design.

For example, what if the similarities in the accused product all relate to prior art elements and functional features? Would the accused product still be infringing? In Lanard Toys, Ltd. v Dolgencorp LLC, the answer was no according to the Federal Circuit.

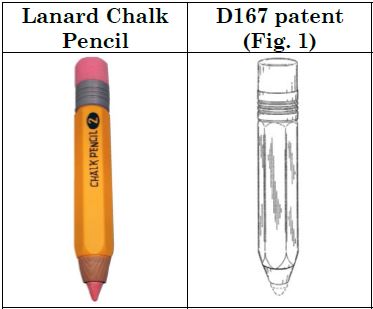

Here are images of the plaintiff’s patented design

Here’s the accused product by the defendant:

At first blush, it might seem like the accused product is rather similar to plaintiff’s US Patent No. D671167. What you do not see are all the prior art references that were considered in order to determine the scope of the protected design. Furthermore, the lower court properly eliminated the functional features from protection, such as the functionality of the conical tapered piece, elongated body, ferrule and eraser.

What does substantially similar mean?

So, there’s a valuable lesson here. You can’t just eyeball a design patent and accused product. A patented design may be substantially limited in scope by both the prior art and functional features. After prior art and functional features are stripped from a design patent, would an accused product be substantially similar to what remains protected?

Or, are the similarities in the accused product limited to either prior art and/or functional features? This was the conclusion in the Lanard case that led to a noninfringement decision.

Can you change a design to avoid infringement?

Plenty of examples show that the mere addition of a label or trademark does not escape design patent infringement. For example, adding a label to a shoe does not avoid design patent infringement. See L.A. Gear, Inc. v. Thom McAn Shoe Co., 988 F.2d 1117 (1993).

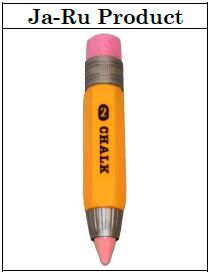

More recently, however, the Federal Circuit held that adding a logo or trademark to a pattern might possibly avoid design patent infringement.

Does getting your own design patent help you avoid infringing other design patents?

When it comes to design patent infringement, is offense the best form of defense? The Columbia vs. Seirus case would suggest that adding distinctive visual features to a patented design might possibly avoid design patent infringement.

While it’s no guarantee that such visual additions can help you escape liability, the noninfringement decision of the Columbia v. Seirus case would encourage competitors to combine an old design with some new visual features. It might make sense, therefore, to file new design patent applications for such modified designs.

How is design patent infringement different than utility patent infringement?

Utility patent infringement is not visual. A line-by-line claim comparison must be performed to determine if an accused product would infringe a utility patent. Therefore, the presence of additional features would not detract from the determination of infringement.

Design patents, however, are entirely visual. And it is this visual comparison that opens the door for ornamental changes and additions to make an accused design look different enough to defend against a design patent infringement claim.

Need to avoid design patent infringement?

Contact US design patent attorney Vic Lin by email at vlin@icaplaw.com or call (949) 223-9623 to see how we can develop and execute a strategy to avoid design patent infringement by obtaining your own design patents.